Megalopolis Review

We’re in need of a great debate about the future!

Note: This article contains spoilers for the film. I recommend not worrying too much about spoilers for this film though.

I love Megalopolis. To be honest, I knew I would love it from the moment I heard the story of its premier: it got a six-minute standing ovation at Cannes, half of which were boos. How could anything that polarizing not be amazing?

And amazing it is. 100% lives up to the hype, despite what the haters will tell you. I think it is my favorite film now. As of this writing, I’ve seen it nine times. It’s not that Megalopolis is the generational work of art it aspired to be, but it’s still beautiful. To be perfectly honest, as a film, it doesn’t really work. I mean, it’s not a good film. But if you abstract a bit further, to art in general, yeah, it’s good art, perhaps great art. The storytelling is incoherent, but that’s OK because the plot is kind of the subtext anyway. The symbolism is the real text.

That is to say, the symbolism is completely devoid of any subtlety. A statue of the lady of justice crumbles as Cesar drives past to symbolize injustice. At one point a character steps onto a tree stump shaped like a swastika to go on a populist tirade. The aesthetics are often sloppy — Coppola fired his VFX team mid-way through production. The messaging might be even sloppier. The film opens with a critique of oligarchic elites attempting to hoard power for themselves, yet the protagonist, a Randian uberman if there ever was one, saves the day and in no way involves the common people in his efforts to create a utopia for them.

That said, a discerning eye, with a bit of squinting, can see it for what it was meant to be — the vision Francis Ford Coppola had in 1977 perhaps. A spiritual successor to Metropolis, homage to Robert Moses (more on this point later), a grand cinematic spectacle, and an inspirational fable for future generations, among other things.

And while it falls short of its extremely lofty ambitions, it does so in such charming and comical ways, that it makes the film even better if anything.

I love its psychedelic insanity, I love its uncanny valley dialog, I love its confusing pacing and overuse of montages, I love how it’s both conservative and progressive at the same time, I love that one the lines during the film’s climax is, “What do you think of this boner I got?” I love the casting, which was absolutely phenomenal. Adam Driver nails Cesar Catalina, Shia Laboeuf as Claudio Crassus is the best I’ve seen him act in any film, and Aubrey Plaza’s Wow Platinum was just incredible.

But what I love most about the film is its call to dream of a better future. This is Coppola’s true intended message, and it isn’t exactly subtle. During his climactic speech, Cesar Catalina literally exclaims that “We’re in need of a great debate about the future! We want every person in the world to take part in that debate.” Instead of releasing the film on blu-ray or streaming, Coppola decided to take it on a summer tour where, after the screening, audience would engage in discussion about the future. Though in reality, this “discussion” was mostly just listening to Coppola go on an unhinged schizo old man rant about his thought about society.

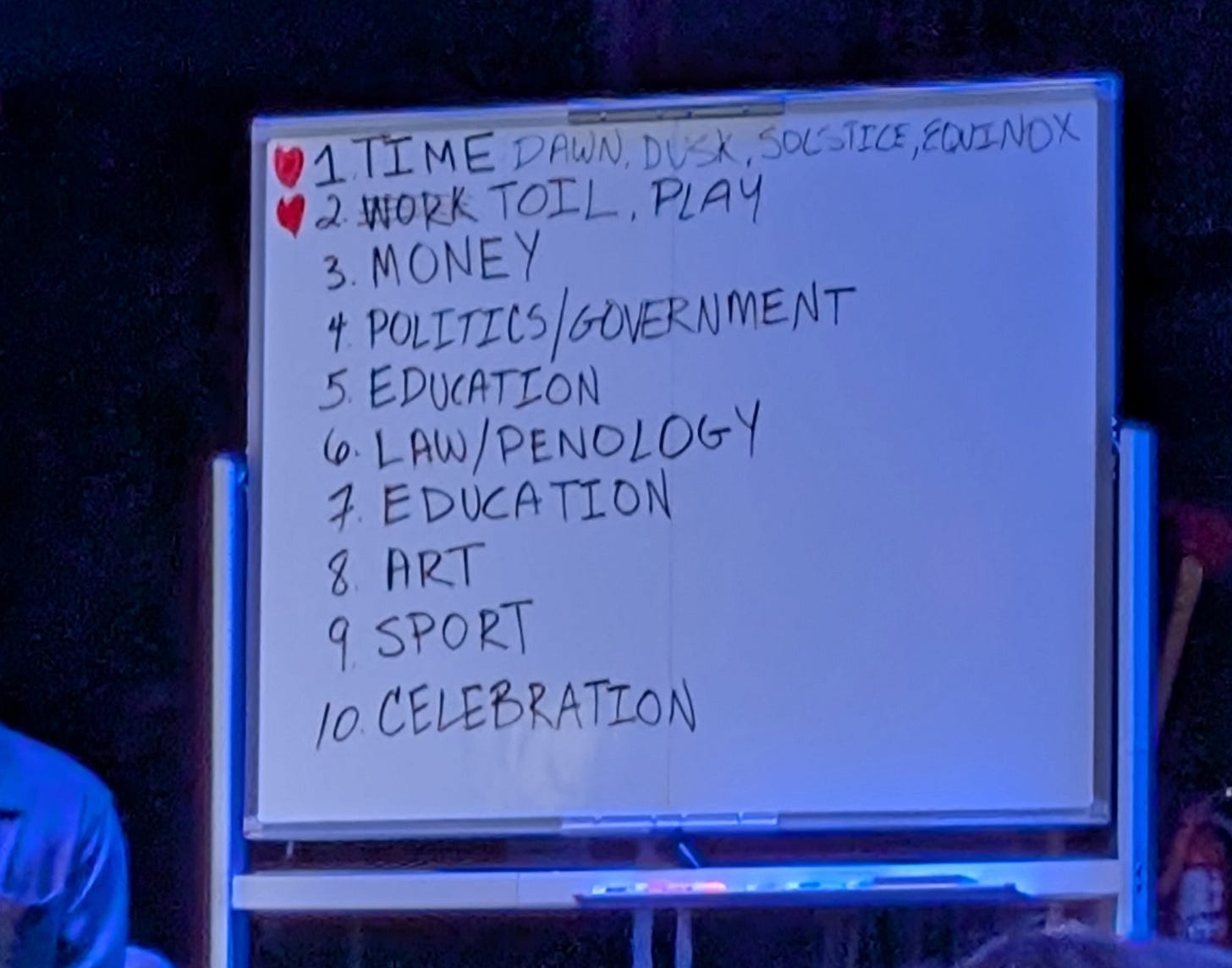

I went to one of these live screenings. After the film, Grace VanderWaal (Vesta Sweetwater) came out and performed her song from the movie, the one about her virginity. Then she sang another song, apparently an original that she wrote just for the summer tour at Mr. Coppola’s request, but which was completely unrelated to the film or any of its themes. After that Francis Ford Coppola took a few questions about the film from the audience before wheeling a white board onto the stage and having his assistant write out a list of concepts.

Then he went on a long, meandering rant where he deconstructed each concept into its positive and negative facets, interspersed with digressions and occasional questions from the audience. He got to point #5 “education” (he skipped over “money”) before the venue eventually kicked everyone out because it was 10PM and the staff wanted to go home. Incidentally, when discussing point #4 “government/politics” Mr. Coppola actually endorsed the idea of sortition, though he never referred to it by that name and seemed completely oblivious to the fact that it’s a real thing that is being done in the modern day.

I raised my hand but sadly Mr. Coppola didn’t call on me, because I really wanted to know more about Cesar Catalina’s relationship to Robert Moses. At one point in his ravings, Coppola mentioned Moses by name, critically. For those familiar with the history of New York City and Long Island, Robert Moses is an infamous figure, responsible for building much of the infrastructure around the city and using highly questionable political methods to do so. His career culminated in a very public political battle with Jane Jacobs, whom Coppola also mentioned, fondly. Why then is the protagonist of his film based on this man whom Coppola clearly detests? Rumor has it that Cesar Catalina was originally supposed to be the main villain of the film and was turned into the protagonist sometime in the late stages of pre-production.

At one point Coppola also ranted about an alt-history theory about how domestication of horses was the true origin of global patriarchy and excoriated the societal oppression of women by men. This feminist theme is certainly not reflected in the film however, given that the only female character with any agency, Wow Platinum, is one of the villains, using sex and hypnosis to manipulate men for personal gain (needless to say she is one of the best characters). Julia Cicero (Nathalie Emmanuel) meanwhile is completely passive, serving only as Cesar’s romantic muse.

This change in the film is clearly one of the main drivers of its overall confused and confusing nature. Cesar is turned into an anti-hero. A tortured soul, still wracked with guilt over the death of his wife, aware but unashamed of his callousness and arrogance, he nonetheless works for the betterment of humanity. Coppola was clearly critical of the Randian ethos during his rant, yet Cesar is clearly a Randian figure — a billionaire nephew to the world’s richest man, he is also a Nobel Prize-winning scientist, the inventor of Megalon, a revolutionary new MacGuffin material out of which he builds Megalopolis, his utopian city of the future. Cesar is a solitary, misunderstood genius, opposed by the staid, cynical status quo represented by mayor Franklyn Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito) and the rapacious elite lust for power and wealth represented by Clodio Crassus, Cesar’s cousin. Through his genius and tenacity, and the support of his new paramour Julia (Franklyn’s daughter), Cesar is able to overcome his enemies and deliver utopia unto the unwashed masses who opposed him in their ignorance.

I don’t think that was quite the message that Coppola intended to convey. The film is clearly critical of wealthy elites. Hamilton Crassus (Jon Voight), the richest man in the world, and his wealthy friends are portrayed as out of touch buffoons throughout the film. The lavish excesses of elites are constantly lampooned, and the deprivation of the poor constantly highlighted. Yet their salvation comes from a lone genius of the most aristocratic pedigree.

I suspect the change to the script was motivated by the election of Donald Trump. His populist, revanchist message must have bothered Coppola a great deal to motivate him to rewrite a script he had been working on for decades. Perhaps he sees the optimistic yet arrogant technocrat as the lesser evil compared to populist demagoguery.

Confused politics and confusing storytelling aside, the core intention of the film is obvious: Francis Ford Coppola wants us to be optimistic about the future. People have become jaded to the idea that the world can be meaningfully improved. This has become the dominant theme of politics in America today. Over the past hundred years or so, we’ve lost our collective dream of societal improvement. The failures of utopian movements of the 20th century — communism, fascism, liberal modernism — led us to abandon the very notion of utopianism entirely. Once again, there is no subtlety about this in the film:

Cicero: Utopias offer no ready-made solutions.

Cesar: Well, they’re not meant to offer solutions,

they’re meant to ask the right questions.

Cicero: Yes, but… utopias turn into dystopias.

Cesar: So, we should just accept this endless conflict that we live in now?

Francis Ford Coppola is calling on us to imagine better futures once more, to start asking questions about how to improve society. Not asking them rhetorically for the purpose of reviving dead ideologies, but actually seeking new answers. Unsurprisingly, this resonates with me. Coppola is asking us: “What is your Megalopolis?”

Dear reader, have you seen your Megalopolis? If you know, you know. I’ve seen mine. If you’ve been following my writing, you probably know about my sortition advocacy. Sortition is my Megalon, and with it I intend to build my Megalopolis. Not alone of course, I’m not a billionaire genius like Cesar Catalina, but I have allies I am building with. There are others with their own grand visions of course. Elon Musk, Audrey Tang, Sam Altman, and more. Such visions used to be more common. Science fiction novels abounded with visions of a better tomorrow. Now, even Star Trek has embraced cynicism in some of its new series, such as Picard.

I’m not sure how deeply considered Coppola’s loose vision was. The city of Megalopolis itself and its institutions are not explored deeply in the film. Megalon, the miracle material used to build the city, and to save Cesar’s life, is also left largely as an enigma. Though what is said about Megalon resonates with some of my thinking.

I believe Megalon is a metaphor for emotionally and psychologically integrated humanity. Megalon is depicted as a psychically resonant substance that is able to tap into core psychological needs and insecurities and reveal them to you. As a built environment, it responds to peoples’ needs before they are even fully consciously aware of them. This combination of traits encompasses what is necessary for true human flourishing. We’ve heard time and again about how atomized people have become. We have lost community, lost third places, lost close friendships and stable family relationships. The human spirit itself is adrift in this age of technocapital. If only there was a way we could come together, to coordinate, to break free from the invisible memetic and institutional chains that bind us.

Those who have been keeping up with advancements in AI and adjacent technology know that big changes are coming. Our world is set for upheaval. Perhaps Megalopolis is one of the ways our collective consciousness is processing this approaching reality.

The discourse around AI, and technology in general, is still motivated by doom and gloom however, outside of a small slice of techno-optimists. This risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. If humanity is to avert disaster, we need to believe that a brighter tomorrow is possible. Megalopolis sadly did not succeed at transmitting that message to the masses, but it was a noble and necessary attempt.

Bonus Content:

These are some extra takes of various temperatures and epistemic statuses that I couldn’t figure out how to work into the main essay. This section will be paywalled once I get around to setting up payments, so enjoy it for free while you can.

Francis Ford Coppola self-inserts

I believe that Mr. Coppola inserted himself into this film not once, not twice, but (at least) three times. During the live event, Coppola readily admitted that he saw himself in Cesar Catalina. Megalopolis (the city) symbolizes Megalopolis (the film), a bold new vision for what film can be. The Hollywood old guard (symbolized Cicero) didn’t believe in this bold vision and refused to fund the movie. Hamilton Crassus too represents Mr. Coppola, who generously funded Megalopolis (the film) out of his own personal fortune just as Crassus funded Megalopolis (the city) at the end of the film. Franklyn Cicero too, however, is a representation of Coppola. I believe he is meant to represent Coppola’s fears and anxieties about the future, but also his love of family. In keeping with the other symbolism in the film, it’s not particularly subtle, as Mayor Cicero reveals to Cesar that his real name is not Franklyn, but Francis.

Baby’s name

The baby’s name/gender is symbolic of FFC’s success/failure to capture his intention with Megalopolis. Francis if he’s a boy, meaning FFC succeeded and Megalopolis was a cultural hit that resonated with audiences. Sunny Hope if she’s a girl, meaning that FFC’s vision failed to resonate with most, and must instead serve as a beacon of hope for the next generation of visionaries.

Cesar’s dead wife

Sunny Hope (Haley Sims), Cesar’s dead wife, is a recurring character in fleeting flashbacks throughout the film. The film’s central plot revolves around him getting over his guilt surrounding her suicide and allowing himself to move on.

The thing is, Cesar totally gaslit his wife to death. Mayor Cicero was 100% right when he said was exonerated “legally, but not morally.” Not with regards to Cesar’s relations with Vesta, but with regards to the death of his wife. The exact details of her suicide are revealed through a brief sequence of Megalon-induced flashbacks that are extremely easy to miss when viewing, especially if you don’t have subtitles on. The flashbacks seem to depict the last conversation between Sunny and Cesar before her death.

CESAR: You found me.

SUNNY: I have good news.

CESAR: What’s that, what’s your good news?

SUNNY: Those cigarettes, Cesar…

Why is there lipstick on the cigarettes?

CESAR: Are you really asking me

why there’s lipstick…

Who’s been in our home again?

…I was at home and not on a jury stand…

SUNNY: Why do you do this?

…where the judge is asking…

SUNNY: Why do you do this?

CESAR: Why do I do what?

SUNNY: You use that great brain of yours.

And you manipulate. And you blame.

CESAR: Why do I use my great brain

to find a bunch of logical things…

SUNNY: And you try to make me feel like I’m the crazy one.

…as opposed to hypothetical situations?

SUNNY: But I’m not the crazy one here.

CESAR: I’m not trying to tell you you’re crazy,

but you’re trying…

SUNNY: You are, you are.

CESAR: How are you not trying to tell me that I’m crazy?

SUNNY: You make me feel that I’m imagining.

It’s not my imagination!

CESAR: It’s so convenient…

I’m so prepared, all I do…

SUNNY: Save your dreaded heart.

Cesar of course admits earlier in the film that his madness drove his wife to kill herself. This scene serves to reestablish the ongoing motif of Cesar’s guilt over his wife’s death. Here though, it’s finally revealed what went down. His wife came home with good news and saw a cigarette with lipstick. Presumably a mistress of Cesar’s left it. Cesar deflects and tries to manipulate Sunny into thinking she’s crazy. Then, she gets in the car and drives off the bridge. We later find out she was pregnant with twins when she died.

Alternate theory: Did Wow Platinum kill Sunny Hope? Perhaps Cesar really was cheating on Sunny with her, but Wow intentionally left the cigarette where Sunny would find it. Or maybe Cesar wasn’t even sleeping with Wow, and she just wanted to break them up so she could have Cesar.

Is Megalopolis humanity’s collective unconscious attempting to prepare for the singularity?

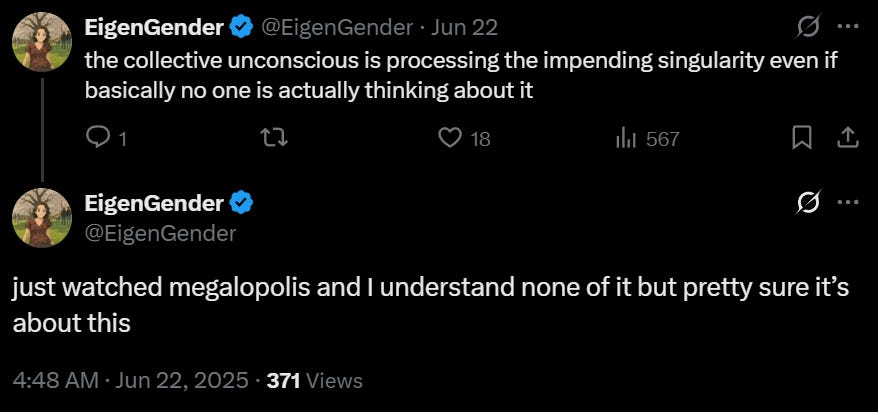

I was intrigued when Eigengender tweeted this because the thought had occurred to me as well.

I think there is something to be said for the idea that great art doesn’t so much come from the minds of great artists as it is the universe speaking through them. That isn’t to say it’s necessarily prophetic, just that one distinguishing feature of a truly great artist is the ability to channel information that a single human mind could not possibly comprehend into a work of art. Maybe Megalopolis is in some way a psychic reverberation of the coming shift. And maybe the properties of Megalon are more significant than they seem, though I won’t get into that here.

Reading this essay makes me really want to see the film! Thank you.

There is something infuriating about someone gleefully enjoying an awful movie.

It's infuriating because I'm immediately jealous.

I haven't seen Megapolis, but seeing you start off the post with concessions like "I mean, its not a good film" primes me to think that all I'd feel is angry FOMO of not being in on the bit.

Even so, I appreciate being taken on this journey to live vicariously through your experience. Thanks for sharing!