What's Left for the Left

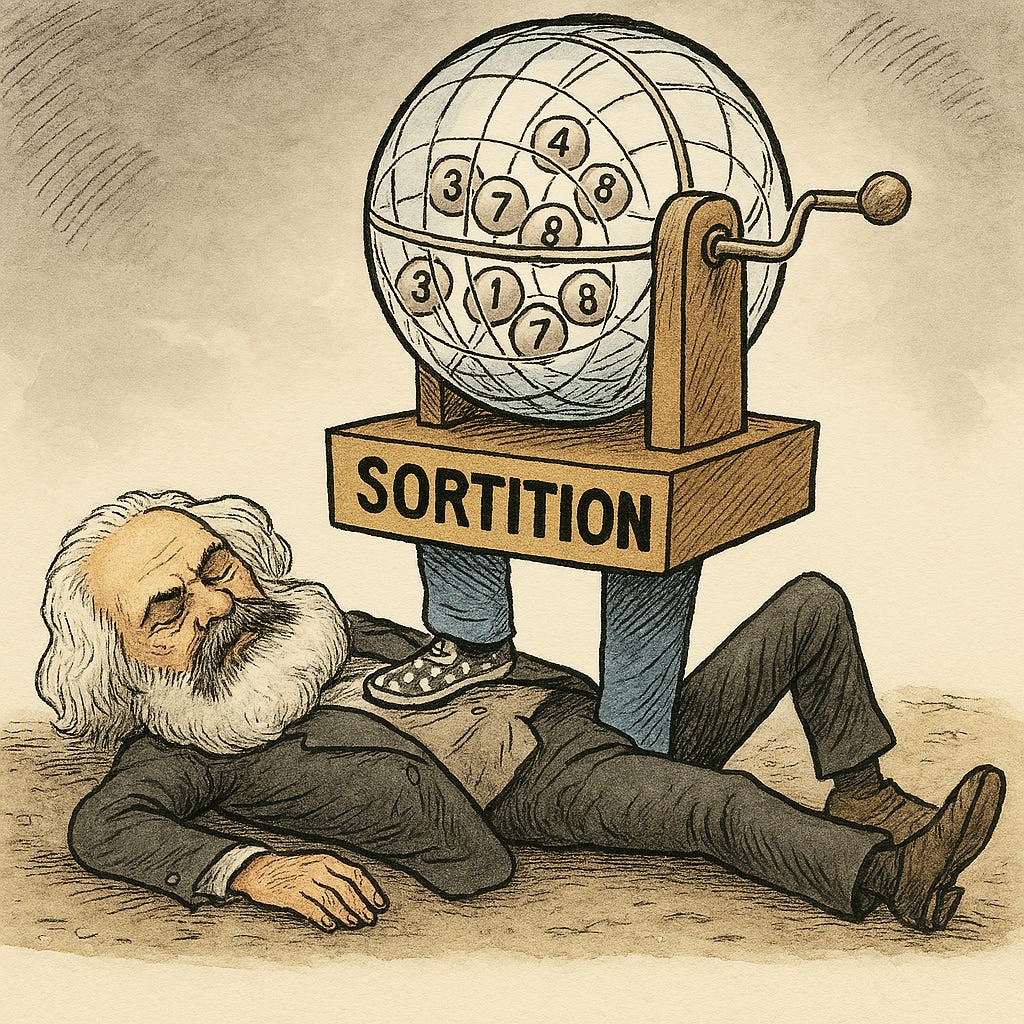

Sortition as a New Ideological Foundation to Fill in for the Failure of Marxism

It's been a rough half-century for the Left. The USSR collapsed, China and Vietnam embraced market economies, two dozen or so Communist regimes fell around the world. Democratic socialist regimes floundered economically, the kibbutzim transitioned to mixed economies, unions in capitalist countries have seen their numbers stagnate or decline. What communes do form in rich countries tend to quickly become cults or succumb to infighting. Some leftist social theories managed to gain significant influence in the West, and left wing parties have managed the occasional minor victory here and there, but for the most part, leftist thought has not fared particularly well over the last 50 years. Perhaps it's time to rethink what Leftism really means.

The problem with all leftist thought begins, of course, with Marx. Specifically, Marx's failure to truly strike at the first principles of class struggle. To understand these first principles, we must strip away the dressings of civilization: the state, tradition, belief systems. To look back to before the dawn of humanity, we must look to our cousins, the chimpanzees, and to mammals with highly sophisticated social systems in general. Do they have class struggle? Yes! It is a primitive form, not as clear as human class, perhaps more aptly called "protoclass", but it is there. What is this most fundamental basis of class distinction that even animals possess? The ability to form alliances. In other words, the capacity for politics. Even without language, apes are able to do this. Among chimpanzees, the alpha is not the largest or the strongest ape, but the most political ape. Those apes who are best at securing and keeping allies reap a greater share of food, grooming, and mates. Those who are worse, get the last pickings. What is that if not class distinction?

This has always been the case for humans as well. Marx failed in his analysis to reach this conclusion. To Marx, economic control over capital is the most ultimate basis for class distinction. He acknowledged the importance of politics to class struggle of course, but ultimately he believed that control over capital was fundamental to class hierarchy and oppressive social structures. This is an error. Ownership of capital is downstream from capacity for politics. Even the violence necessary for primitive accumulation under pre-capitalist social organization is downstream from capacity for politics. The most fundamental basis of social organization, and therefore class distinction is, and always has been, the capacity for politics. Without the ability to form alliances, humans have no power, and therefore no ability to obtain or retain capital. The state is nothing more than a legal fiction made up of complex webs of alliances woven together by norms and procedures. The state is made of politics. The very concept of ownership itself exists only by virtue of politics. One cannot own something in a vacuum; ownership is merely the right to exclude, enforced by others. Capital plays a recursive role in politics yes, in that it can be used to facilitate the formation of alliances, but it is still merely instrumental to power rather than fundamental. Capital facilitates power only because it facilitates coordination between individuals. Coordination is the ultimate root of power, and politics is coordination.

It is precisely this essential misunderstanding that has been the cause of most of leftism's failures over the past 150 years. Communists claim to want a classless society, and yet every time a group of communists bands together, they spontaneously form class structure! Instead of the bourgeoise vs. the proletariat, it becomes the Party vs the proletariat, or the Marxist-Leninists vs. the anarcho-communists, or some other conflict. The denial of the fundamentality of politics to class distinction, combined with the abolition of formal hierarchies, leads invariably to the formation of informal--and thereby uncontestable--hierarchies. Revolutionary vanguards fail to give up power to preliterate committees, anarchist communes devolve into factionalism, infighting, and failures to coordinate against external threats; it's a story as old as the earliest intellectual seeds of leftism in revolutionary France. Without an understanding of the ultimate nature of class distinction, humans can't help but reinvent it again and again. But with an understanding? Ah, perhaps then we may yet stand a chance!

If the ability to form alliances, to coordinate, with other individuals is the fundamental root of power, then the only way to democratize power, and thereby eventually abolish class distinction, is to supplant natural alliance-formation mechanisms. They must be supplanted in a bottom-up fashion, as any attempt to suppress established alliance-formation mechanisms in a top-down fashion would require the creation of alliances based in class structure. Supplant them with what though? Why, with sortition! Democracy by Assembly. Ultimate coordinating authority must rest with assemblies selected by lottery. Any other selection method beside random chance risks the infiltration of humanity's instinctual politicking. Even selection by lot does not totally eliminate it, as randomly selected delegates would still engage in politicking among themselves, though this can be mitigated somewhat. Selection by lot would however eliminate the compound effect of politicking--that tendency for alliances to stack upon themselves and grow into great beasts known as special interest institutions, and the leviathans that are states. These deliberative bodies, known as civic assemblies, would have the ability to coordinate without the hierarchy that is inherent to elections.

Why sortition? Why not go further and establish government by plebiscite? Let everyone vote on everything! I shouldn't need to point out the problems with this. The common worker is busy with the needs of daily life, policy is complex. How are they to find time for the thorough research needed to weigh in intelligently on all manner of political question? We know by now how such a system would unfold: influential members of the community, particularly those able to leverage media institutions, would end up dictating how people vote. People would form into factions and vote based on the influencers they aligned with most. Essentially, an informal form of political parties would be created, and a small number of influential individuals would wield disproportionate power. By selecting a random representative sample of the population and giving them the time and resources to thoroughly research and deliberate, we vest ultimate authority over policy with common people.

The modern sortition movement which has been oriented around such deliberative assemblies has been going for about 30 years and over 1000 such assemblies have been held around the world so far. The overwhelming majority of these have been local and purely advisory, but they have had meaningful impacts nonetheless. The goal of the movement however, is to vest such assemblies with real, direct power. There is not necessarily a strict need to make them mandatory like juries, though that is a possibility. Most such assemblies have been voluntary (typically with financial compensation), with stratified sampling used to account for selection bias and maintain demographic representativeness of the broader population. This model of government by randomly selected citizens is not as radical as it may seem. Sortition was the basis of how Athens was governed from 507BCE to 322BCE. The boule, a council of 500 citizens selected by lottery, was the primary seat of decision-making authority. Local magistrates were also selected by lot. This period during which Athens was governed primarily by sortition encompassed its golden age and the lives and careers of many of the most famous philosophers in history.

Transitioning to government by civic assemblies would not be a mere exchange of power structures, it would be a complete redefinition of the social and political order. Current republican governments are structured as hierarchies largely out of necessity. The public votes to elect a legislature and executive, who then proceed to appoint the various officials tasked with the day-to-day tasks of actual governance. Legislators vote on laws, but they do not usually write them themselves, they hire staffers to do that. The executive appoints the heads of agencies or ministries, who then hire bureaucrats through ordinary employment processes. In many jurisdictions, judges and prosecutors are likewise appointed, then tasked with hiring support staff. The common people, when they have grievances, must grovel to merely be heard by the elected officials who nominally serve them.

The assumption of electoralism is that the public voted for certain officials, therefore they consent to their rule, and therefore the officials are entitled to appoint whomever they see fit to run the government. But in no election do would-be governors or legislators submit public lists of all their planned appointments for the voters to review. Indeed, they seldom even have such complete lists until after the election. In practice, the consent given by the voters is not informed consent, its legitimacy is illusory.

Furthermore, why must a single executive, or even a particular slate of legislators, be given the power over so many appointments and policy decisions? It's not as though elected officials are chosen for having deep knowledge of the myriad subjects related to governance. It's done for logistical reasons of course, as it would be impractical to elect multiple legislatures at once to govern each area of society. Democracy by assembly obviates the need for centralized, hierarchical bureaucracy entirely. High level officials could each be appointed by a dedicated assembly devoted to carefully vetting candidates in a process that would more closely resemble an ordinary job interview than an election. Assemblies could be convened to produce legislation or policy guidance in one specific area, ensuring that each one is able to do the careful research and deliberation necessary to produce thoughtful policy. Even to the degree that assemblies may decide that an executive is necessary, only those functions which could be fulfilled exclusively by an executive, such as decisive leadership during emergencies, would be delegated to them.

In other words, there would be no need for states as they exist today, as moderately centralized hierarchies. The coordination capacity enabled by civic assemblies would not only be more equitably distributed, it would also be superior in quality to the point of finally enabling the dream of a de facto stateless society. In order for the people to trust such assemblies however, they would have to become so commonplace that the average person could expect to be summoned to serve once every few years, similar to jury duty. Hannah Arendt argued that humans have an existential need to engage in politics. Having seen the emotion of delegates giving their closing statements at civic assemblies, I agree. Delegates frequently report their service to be one of the most meaningful events in their lives. For many, it's the first time they felt agency over something significant outside of their own lives. Few people feel that way from voting. Delegates also tend to come away from their service permanently more engaged with their communities. There are records of ancient Athenians selected for the boule who felt similarly.

Most people today are so alienated from real political agency that they can scarcely imagine it. Individual votes are so diluted that any rational individual can understand they don't really matter. Politicians at town halls look down upon their constituents with pity at best, contempt at worst. When everyday people are given the ability to directly participate in power, the result is nothing short of Revolutionary.

Revolution is, after all, still the goal. The upending of the social order promised falsely by Marxism will come to pass in a different form. Marx failed to recognize the true source of power, and thus his followers failed to redistribute it. The Revolution failed, and today only a few ideological hangers on remain, like zombified soldiers still wearing insignias from a long-ended war.

I wish to be forthright. I personally do not actually care about abolishing class distinction. I do not call myself left, or right, or center. I am a coordinationist. I believe in maximizing social coordination. That is to say, I want to maximize the ability to organize society to meet the preferences and meta-preferences of the greatest number of people. I believe that this is the true path to human flourishing. That said, if you care about abolishing class distinction, democracy by assembly is a necessary step, as I have explained. If you care about abolishing the state, democracy by assembly is necessary.

The Communists foolishly thought that they could improve society by reducing coordination. They didn't think of it that way, but it is what they did, in their attempt to suppress market economies. Marx correctly recognized the ways in which markets are an effective but exploitative coordination mechanism. However, the solution of his followers was to abolish markets and replace them with a hypothetical "better" coordination mechanism which no one ever managed to successfully instantiate. The unsuccessful attempts killed or impoverished millions. Marx failed to recognize that the exploitative aspects of markets are simply coordination failures, and that the solution to exploitation and injustice was to increase the coordination capacity of the exploited.

Syndicalists and other more market-oriented leftists have failed to gain traction as well. On the economic right, you don't see successful libertarian societies either. Markets are useful but imperfect coordination systems. States tend to be even worse at coordinating at scale than completely non-agentic market mechanisms, though states can better coordinate in some ways markets often fail to, such as national defense. Overall, state intervention is a poor patch to the coordination failures of markets. Social experiments that attempted function without either markets or states have seldom lasted more than a few years. On the other hand, Athenian sortition-based democracy stood for nearly 200 years, and oversaw a period that produced many of the greatest thinkers in ancient history, despite the primitive design of their system compared to modern deliberative assemblies. We don't have to guess whether sortition works, we merely have to remember that it does.

It is time to Remember. Revolution can only be realized through right understanding of power. If you want to overturn the corrupt, exploitative social order and bring about a just, equitable society, join the cause of sortition.

This is the second post in a multi-part series about how sortition could be useful to a variety of different ideologies. Find the first post here: The Case for a Technocratic Doge: What techno-monarchism can learn from the Venetian Republic

are you very familiar with kibbutzim? i stayed on one for two weeks in college, but only learned a few months ago that had georgist connections.